What are Cognitive Distortions?

And how can we try to reduce them?

“Nobody likes me.”

“I just failed that exam. I am such a failure in life.”

“I can’t trust anyone; everyone is going to end up hurting me.”

Credit: Just Passing Time

Do these thoughts sound familiar to you?

They are all prime examples of cognitive distortions – thought patterns that can cause you to perceive yourself, others, and the world in inaccurate and negative ways!

Cognitive distortions are habitual errors in thinking and most of us experience them from time to time. Although we develop these cognitive distortions to help cope with adverse life events, these thoughts might not be rational nor healthy for us in the long-term, as they can increase the risk for anxiety, depression, and other relationship difficulties.

Understanding Cognitive Distortions: A Comprehensive Guide

The different types of cognitive distortions

There are at least 10 different types of cognitive distortions we experience. These include:

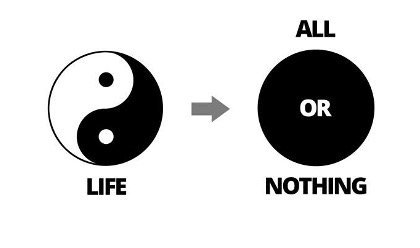

1. All-or-nothing thinking

“If I am not a total success, I am a failure.”

Also known as “polarised” or “black-and-white” thinking, all-or-nothing thinking occurs when we habitually think in extremes, viewing a situation in only two categories instead of on a continuum.

This kind of cognitive distortion is unrealistic and often unhelpful for us because most of the time, reality exists somewhere between the two extremes.

2. Catastrophizing

“I stuttered so much during the job interview, I must surely be rejected. I will never be able to get a job.”

Also called “fortune-telling”, catastrophizing involves assuming the worst when faced with uncertainties, predicting the future negatively without considering other, more likely outcomes. When we catastrophize, ordinary worries can quickly escalate.

While it is easy to dismiss catastrophizing as an over-reaction, people who have developed this cognitive distortion may have experienced repeated adverse life events, such as childhood trauma, so regularly that they have learnt to fear the worst in many situations as a coping strategy.

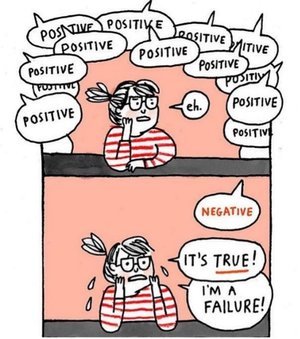

3. Disqualifying or discounting the positive

“I might have scored well on that exam, but that does not mean I am competent; I just got lucky.”

A negative bias in thinking, you unreasonably tell yourself that your positive experiences, achievements, or qualities do not count, explaining them away as a fluke or abnormality. When we do this often and believe that we have no control over our circumstances, this thinking can diminish our motivation and cultivate a sense of “learned helplessness”.

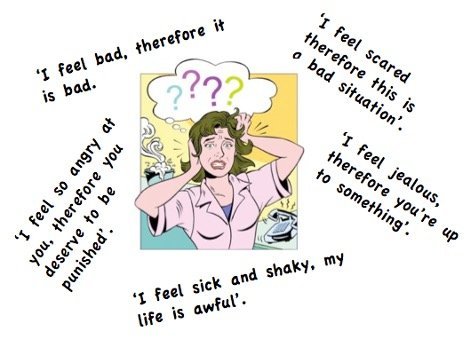

4. Emotional Reasoning

“I feel like a failure, therefore I must be a failure, otherwise why would I feel this way?”

Emotional reasoning is the false belief that your emotions are the truth, and they are an accurate depiction of reality, whilst ignoring or dismissing evidence that suggests the contrary. Although it is important to listen to, validate and express your emotions, it is equally crucial to judge reality based on factual evidence! This is a common cognitive distortion even amongst people without anxiety or depression.

5. Labeling

“Since she arrived late, she must be a lazy and irresponsible person.”

You put a fixed, global label on yourself or others without considering that the evidence might more reasonably lead to a less negative conclusion. This often happens when you judge and then define yourself or others based on an isolated event. The labels assigned are usually negative and extreme.

Assigning labels to others can impact how you interact with them. This, in turn, could create friction in your relationships. When you assign those labels to yourself, it can also hurt your self-esteem and confidence, leading you to feel insecure and anxious.

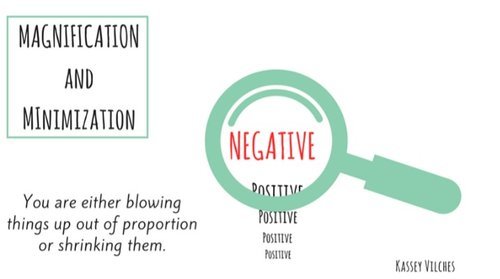

6. Magnification / Minimization

“Getting a mediocre evaluation just proves how inadequate I am.” -- Magnification

“Getting high marks doesn’t mean I’m smart.” -- Minimization

Have you heard the popular phrase, “Don’t make a mountain out of a molehill?” Well, there is a reason why many often do that! When you evaluate yourself, another person, or a situation, you might unreasonably magnify the negative and/or minimize the positive.

7. Mental Filter

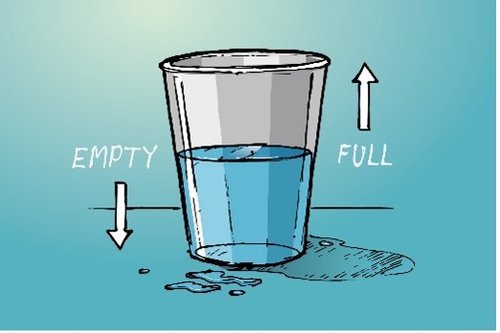

Is the glass of water half full or half empty?

“Because I got one low rating on my evaluation [which also contained several high ratings], it means I’m not performing good enough.”

Mental filter is also known as selective abstraction when you dwell excessively on one negative detail instead of seeing the whole picture. Even if there are more positive aspects than negative in a situation or person, you focus on the negatives exclusively. Interpreting circumstances using a negative mental filter is not only inaccurate, but it can also worsen anxiety and depression symptoms. There is research that having a negative perspective of yourself and your future can cause feelings of hopelessness. These thoughts can become extreme enough to even trigger suicidal thoughts.

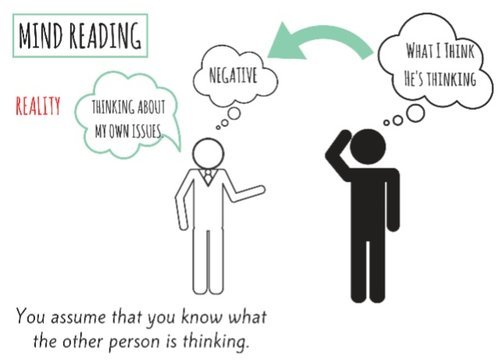

8. Mind Reading

“What a grim expression he has! I must have done something bad to offend him! This must be why he seemed so distant from me nowadays.”

Also known as “jumping to conclusions”, mind reading involves you believing that you know what others are thinking or feeling, while failing to consider other evidence or more likely possibilities. Then, you react to your assumption. This thinking error is often in response to a persistent thought or concern of yours.

9. Overgeneralization

“Because I felt so uncomfortable and awkward during the meeting, I don’t have what it takes to make friends. Oh no, I am destined to be alone!”

When we overgeneralize, we tend to make a negative conclusion about one event and then incorrectly apply that conclusion across other different situations in the future. Overgeneralisation is associated with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and other anxiety disorders.

10. Personalisation

“My parents are fighting again. It’s all my fault.”

One of the most common thinking errors is taking things personally when they are not connected to or caused by you at all. You might be engaging in personalisation when you blame yourself for negative circumstances that are not your fault or are beyond your control. Another instance is when you incorrectly believe you have been intentionally excluded or targeted, without considering more plausible explanations for others’ behaviours. This distortion is associated with heightened anxiety and depression.

11. “Should” and “Must” statements

“It’s unacceptable that I was late – I should always be on time.”

These imperatives are subjective ironclad rules you set for yourself and others without considering the specifics of a circumstance. You have a precise, fixed idea of how you or others should or must behave with no exceptions, and you overestimate how bad it is that these expectations are not met. Yet when circumstances change, and things do not happen the way you want them to – they really depend on many factors – you feel extremely disappointed, angry, or upset.

12. Tunnel Vision

“My life sucks. I have the worst life.”

Just like being in a dark, isolated tunnel, you only see the negative aspects of a situation when you have tunnel vision.

How to reduce cognitive distortions: A guide

Remember that it’s often not the events but your thoughts that upset you in many instances. You might not be able to change the events, but you can work on redirecting your thoughts!

What do you see these thinking errors as having in common? Does it strike you that a common thread among these distorted automatic thoughts is the failure to take in all known information and to explore realistic outcomes based on evidence?

The good news is that cognitive distortions can be corrected over time. Here are some steps you can take if you want to change thought patterns that may not be helpful.

Steps to Identify and Challenge Distorted Thoughts

Ψ Identify the distorted thought: the first step to change

When you notice your self-talk is causing you anxiety or worsening your mood, you can practise mindfulness and recognise what kind of cognitive distortion is taking place.

Ψ Conduct a reality check

Ask yourself if your thoughts are really accurate and check if there is any existing evidence that supports or contradicts it.

Ψ Reframing the situation

Look for alternative explanations, objective evidence, and shades of grey to broaden your interpretations.

It might also be helpful to create a thought record by writing down your original thought, followed by three or four alternative explanations based on the evidence available to challenge the cognitive distortions.

Example: Instead of thinking “I have a miserable life since all my plans are ruined”, try reframing your thoughts to “It’s okay; it’s just a bad day, not a bad life. Plans change and I can adapt.”

Ψ Putting things in perspective

Even if your negative thoughts about yourself, others or the situation are accurate, ask yourself if it will still be important in the grand scheme of things, and whether it will matter a week or month from now. Chances are, they most likely won’t.

Ψ Perform a cost-benefit analysis of your thoughts

Behaviours are often reinforced and repeated when they are perceived to be beneficial in some way.

If you find yourself often engaging in cognitive distortions, you might find it helpful to analyse how your thinking patterns have helped you cope in the past. Do they invoke a sense of control in situations where you feel helpless? Or do they allow you to avoid taking responsibility or necessary risks?

You can also identify the potential costs are of engaging in cognitive distortions. Weighing the pros and cons of your distorted thinking might motivate you to replace them with more balanced, positive thoughts.

Ψ The role of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)

What is CBT? CBT is an evidence-based psychotherapy where people learn to identify, challenge and change unhealthy thinking patterns. If you need additional guidance in identifying and altering cognitive distortions, then you may find CBT helpful.

CBT usually focuses on specific goals. It generally takes place for a predetermined number of sessions and may take a few weeks to a few months to see results.

You may consider looking for a therapist who is properly certified and trained in CBT, and ideally has experience addressing your type of thinking pattern or issue.

In summary, cognitive distortions are negative thinking patterns that impact how you see yourself and others. When our thoughts are distorted, our emotions are, too. By becoming aware and redirecting these negative thoughts, you can significantly improve your mood and quality of life.

Reach out to a mental health professional if you need additional help!